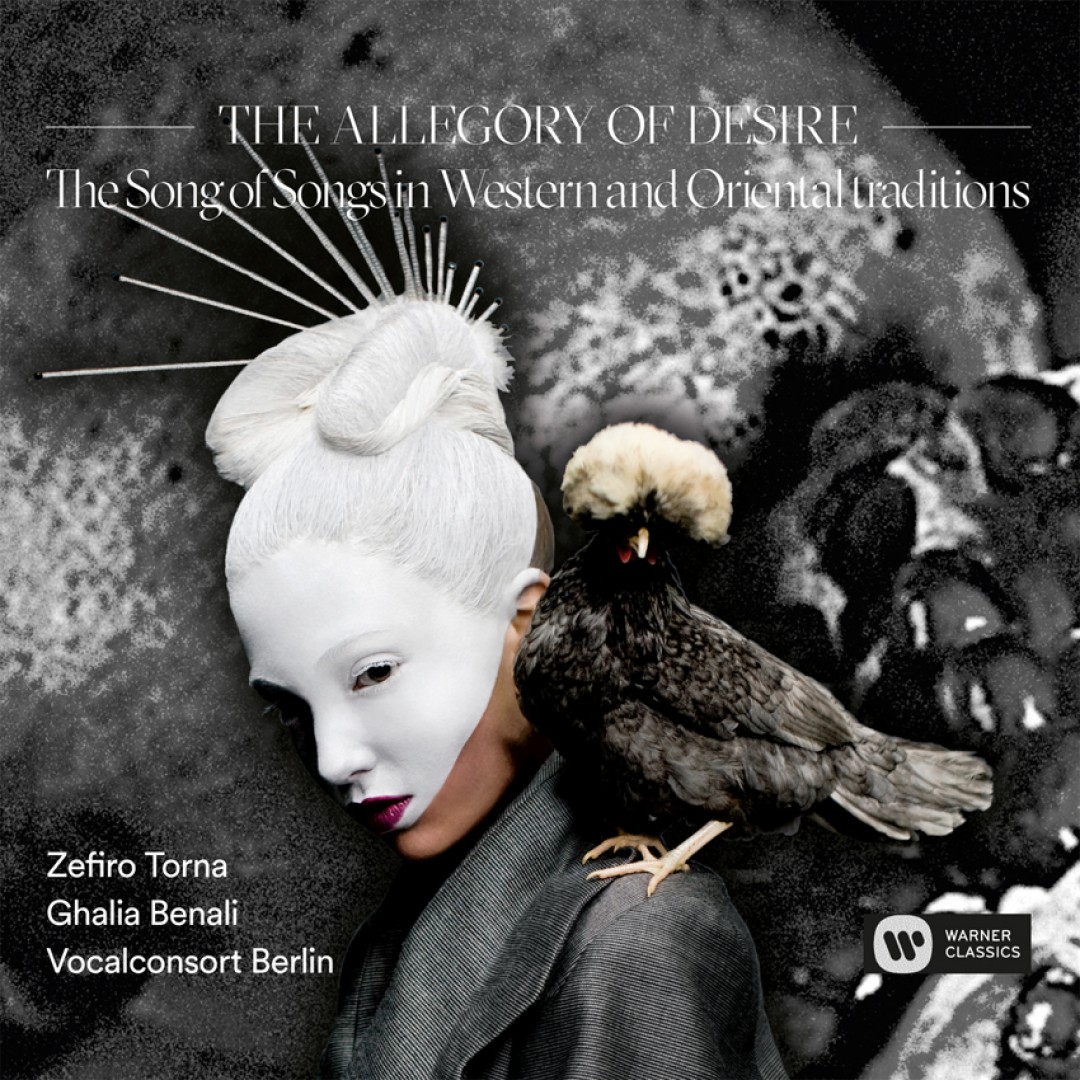

The Allegory of Desire

— The Song of Songs in Western and Oriental traditions (2016)

Zefiro Torna – Vocalconsort Berlin – Ghalia Benali

- Johann Christoph Bach (1642-1702) - Meine Freundin, du bist schön (from ‘Hochzeitskantate’/Altbachisches Archiv)

- John Dunstable (1390-1453) - Quam pulchra es

- Hildegard von Bingen (1098 - 1179) - Ghalia Benali / Text: Abdalla Ghoneem (Egypt,1990) - Favus distillans - Mw'soul

- Guillaume de Machaut (c.1300-1377) - Maugré mon cuer - de ma dolour confortés - Quia amore langueo

- Ghalia Benali (1968) / Text: Abdalla Ghoneem & Ghalia Benali - Last embrace

- Heinrich Schütz (1585 - 1672) - Ego dormio

- Ghalia Benali / Text: Zakaria.M (Egypt, 1992) - Dry Veins

- Orlandus Lassus (1532-1594) - Veni dilecti

- Allessandro Grandi (1586-1630) - O, quam tu pulchra es

- Riad Al Sunbaty (Egypt 1906-1981) for Oum Kalthoum / Text: Rābiʻa al-ʻAdawiyya (Iraq 8th C) - Araftu'l Hawa

- Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) - Pulchra es (from 'Vespro della beata Vergine')

- Dietrich Buxtehude (c.1637-1707) - Ad latus - Surge amica mea (from 'Membra Jesu nostri')

- Giovanni Felice Sances (c.1600-1679) - Vulnerasti cor meum

- Trad. (Iraq 9th C, Andalusia 14th C) - Lama Bada

- Johann Christoph Bach - Mein Freund ist mein (chaconne) from the cantata 'Meine Freundin, du bist schön'

- Ghalia Benali - Dama dai'man

The Hebrew Bible contains an extremely mysterious book known as the Song of Salomon, Canticle of Canticles or the Song of Songs. The book reads like a compilation of poems thematically centered around the theme of human love. The main characters are two lovers of the opposite sex. The poetry is rich in its imagery, often plainly erotic and suggestive. The Song of Songs is set in a sublimated world, it can be seen as an allegory for God's love and as a drive for mysticism. For centuries it has formed an inspiration for numerous oriental and western artists as well as scientists.

Zefiro Torna created this exceptional program in 2013, together with Vocalconsort Berlin and Tunisian singer and artist Ghalia Benali. In this program, single voiced madrigals with instrumental accompaniment, vocal duets and trios, a women's choir and polyphonic settings by composers such as von Bingen, de Machaut, Dunstable, Agricola, Lassus, Grandi, Sances, Monteverdi, Schütz, Buxtehude and J.Ch. Bach interact with traditional Arab songs, narrating texts by ‘Sufi’ poets and by a new generation of poets such as the Egyptian Abdallah Ghoneem. Creating an inspiring dialogue between cultures and history, ‘The Allegory of Desire’ bridges the distance between sacrality and humanity.

During the last couple of years, they gained success on prestigious podiums in Brussels, Berlin, Hamburg, Winterthur, Sevilla, Vilnius and Amsterdam. ‘The Allegory of Desire’ was released by Warner Classics in October 2016.

Zefiro Torna

Cécile Kempenaers soprano

Griet De Geyter soprano

Jowan Merckx flutes, percussion

Romina Lischka viola da gamba, Indian chant

Jurgen De bruyn lute, theorbo, artistic direction

Vocalconsort Berlin

Verena Gropper soprano

Anne Bierwirth alto

Stephan Gähler tenor

Johannes Klugling tenor

Christoph Drescher bass

Ghalia Benali Arabic chant, compositions

Musical supervision: Manuel Mohino

Audio recording, mixing and editing: Manuel Mohino

Booklet text: Ilja Stephan & Jurgen De bruyn

Photograph cover: Lieven Dirckx

Photographs booklet: Sebastian Bolesch

Artwork: Jef Cuypers

Production Warner Music: Brigitte Ghyselen

Recorded: June 2016, Eglise Saint-Rémi, Franc-Waret

Released by Warner Classics

Booklet lines

‘Love means bringing people together, despite the differences or distance between them.’ With these words, Ghalia Benali announced the international concert project The Allegory of Desire on various social media. It is precisely in that spirit that this programme, a collaboration with Vocalconsort Berlin and Zefiro Torna, combines five centuries of settings of the Song of Songs by European composers with traditional and contemporary Arabic songs about desire, love and nostalgia. Its emotional horizon ranges from the sensuously erotic to the mystical and spiritual.

Interpretations of love

Those who take the Song of Songs (or Canticle of Canticles) from the Old Testament at face value, discover a dialogue between two young lovers: the Jewish king Solomon and his chosen dark bride of Shulam. They can hardly wait to disappear into the idealized, fertile landscape of the vineyard together, in order to enjoy each other’s bodies. This libidinous desire is brought to life by the sensuous imagery in verses such as ‘Your navel is perfectly formed like a goblet filled with mixed wine. Between your thighs lies a mound of wheat bordered with lilies. Your breasts are like two fawns, twin fawns of a gazelle.’ Or, as the male protagonist is described: ‘His eyes are like doves by the water streams, washed in milk, mounted like jewels. His cheeks are like beds of spice yielding perfume.’ Johann Christoph Bach built a sounding monument to this light, sensuous reading of the Song of Songs with his Hochzeitskantate, of which two movements frame this programme. The cantata text combines quotations from the Canticle of Canticles in such a way that they form a continuous story: a couple is burning with impatience to be together at last, but first they must attend to a few cheerfully festive guests. On the words ‘Mein Freund, komme (…) / Ich komm, meine Schwester (…)’, Johann Christoph paints a musical picture of temptation and expectation through a suggestive game of closely interwoven echoes. Subsequently, the composer illustrates the bride’s walk to the love garden, in an obsessively progressing chaconne accompanied by solo violin – a symbol of the soul.

In addition to this ‘naïve’ reading, there are several theological interpretations of the Song of Songs, in which erotic, physical intimacy acquires meaning as an allegory of mental, spiritual unity between the Jewish people and Jahweh. In the christological-ecclesiological interpretation, the church was thought of as the bride, and Christ as the groom. In the ascetic-mystical reading, however, the role of the bride was attributed to the soul. Finally, the mariological interpretation identified Maria with the lover from the Song of Songs.

An impressive example of the ascetic-mystical interpretation is Dietrich Buxtehude’s passion cantata Membra Jesu nostri from 1680: in this work, the soul of the believer and the Redeemer have an intimate conversation on the cross. Buxtehude devoted each of the seven cantata movements to a different part of the crucified body. Every movement is constructed according to the same scheme: a chorus with lyrics from the Song of Songs is followed by three arias meditating on the biblical quotation. It was the 12th-century St Bernard of Clairvaux who laid the foundations for a mystical interpretation of the Canticle of Canticles with his 86 sermons on this Bible book.

For I am sick with love

Clairvaux pointed out to his audience that the ‘communion of the divine word with the soul’ is not to be imagined as ‘a physical phenomenon or something from your fantasy’. Still, the similarities between sexual and spiritual ecstasy have never been formulated as explicitly as in the bridal mysticism of 13th-century German nuns, who were inspired by St Bernard. For instance, in her book Das fließende Licht der Gottheit, Mechthild von Magdeburg begged: ‘Eia Herre minne mich sehr, / und minne mich oft und lange!’ One of the precursors of this type of female mysticism was Hildegard

von Bingen. She wrote a series of songs in praise of St Ursula, who according to legend was killed by the Huns, together with 11.000 virgins. The learned poet used images from the Song of Songs to sing the praises of the martyr.

With his motet Maugré mon cuer, the 14th-century French poet and composer Guillaume de Machaut was one of the first artists to emphasize the ‘self’, thus showing himself to be a modern, ironic mind. In the upper part of his polytextual motet for three voices, he defends his sceptical take on love: ‘In defiance of my heart and emotions, they want me to say that I am relieved by True Love.’ The lyrics of the middle voice seem to claim the exact opposite. Here, the poet imagines himself to be a happy lover, ‘equipped with joy, mercy, compassion.’ Only in the last sentence, love turns out to give him nothing but sorrow and misery. In the tenor a sentence from the Song of Songs resounds as a cantus firmus in long notes: ‘For I am sick with love.’

This programme invites the listener to compare how different composers have interpreted the Song of Songs in different times. For instance, Bach and Buxtehude – the aforementioned protestant masters of the baroque – rub shoulders with medieval motet composers such as Machaut and Dunstable. As a herald of the baroque, the Franco-Flemish renaissance composer Orlandus Lassus – deemed ‘divine’ by his contemporaries – achieves a brilliant synthesis between ratio and affect in the motet Veni dilecte mi. In subtle ways, he translates the flourishing of nature – ‘videamus si floruit vinea’ – into melismatic polyphony. Grandi, Monteverdi, Sances and Schütz also based their interpretations of the amorous dialogue on the psychological realism of the Italian madrigal style, showing full mastery of the rhetorical palette of the early baroque. Monteverdi’s setting of Pulchra es for two sopranos, from his monumental 1610 Vespers, is a fine baroque example of a mariological reading of the Song of Songs. Virtuosic passaggi symbolize the sighs of desire. Alessandro Grandi, Monteverdi’s Kapellmeister and assistant at the Venetian basilica of San Marco, closely shadows the emotional oscillations of the text in his monodic motet O quam tu pulchra es. At the exclamations ‘come’ and ‘stand up’, the music shifts to a stirring triple metre. Grandi takes harmonically daring steps in the sentence that also underpinned Machaut’s pessimistic motet: ‘quia amore langueo’, ‘for I am sick with love’. Sances’s love duet Vulnerasti cor meum turns to a festive dance measure on the words ‘Veni di Libanon’. Finally, Heinrich Schütz applied the figurative, theatrical language of the Venetians to the sacred motet. In Ego dormio, for example, he uses melodic motifs and rhythmical figures to depict sleep, the heart’s unrest and hair bedewed by night.

The female perspective

Most biblical protagonists are men; most Bible books are named after men. One of the extraordinary aspects of the Song of Songs is that several long passages are written from a female perspective. Many of the songs juxtaposed by Ghalia Benali with the Canticle of Canticles explore that female perspective further. She has asked a new generation of Arabic poets, among whom the Egyptian Abdalla Ghoneem, to reinterpret the poetry of the Song of Songs. Poems set by Benali, such as Mw’soul, Last embrace and Dry veins speak of desire, nostalgia, wandering souls, delirium and intoxication.

The poetry in this programme has a common denominator: each of the songs treats sensual, erotic love as an allegory of spiritual love (as well). In the Islamic world, the 8th-century Iraqi Sufi mystic Rābiʻa al-ʻAdawiyya was one of the first representatives of this poetic style. With its strict rhyme scheme, the ‘ghazal’ has proved its worth for centuries as a literary form in which the love for God and for the world can be captured in words. This poetic form originated in ancient Arabia and was

developed into a complex system by 13th- and 14th-century Persian poets. It reached a late bloom in 16th-century India, which was ruled at the time by the Islamic Mogul emperors. Three hundred years later, German poets such as Rückert and Storm fell under the spell of this poetic form. Thus, in the ‘ghazal’, a true exchange materialized, traversing and transcending the whole world, across times and cultures, exactly as Goethe, who was fascinated by the Orient, imagined when he spoke of ‘world literature’.

Three of the songs selected by Ghalia Benali reflect the broad dissemination of erotic-religious poetry in the Islamic world. Araftu’l Hawa ties in with a tradition leading back to Oum Kalthoum – one of Egypt’s most renowned singers from the previous century. In the 1950s, at the height of her fame, Kalthoum participated in a radio show and a film on the life of the aforementioned al-’Adawiyya by singing a series of songs with lyrics by the Sufi mystic. Lama Bada is an Andalusian folk song from the 14th century, with literary roots stretching all the way back to 9th-century Persia. The mesmerizing Dama da’iman (‘Last eternity’) builds a bridge between Arabia and India, and concludes by wondering if the lovers will ever be reunited.

Ilja Stephan/Jurgen De bruyn

Translation: Katherina Lindekens